Forespar's Point of View

Blogging About Life on the WaterTag Archives: Forespar

Hunt Made Us Go Faster

C. Raymond Hunt  had one of the most significant impacts on modern boating, right up there with Ole Evinrude and Olin Stephens.

had one of the most significant impacts on modern boating, right up there with Ole Evinrude and Olin Stephens.

Hunt was the naval architect credited with designing the first deep-vee hull(s). He started working with sailboat and lobster boat designs in the 1930’s in Massachusetts, and experimenting with deeper deadrise hulls for powerboats in the 40’s. That led to the revolution in powerboats, with deep-vee designs creating boats that knife through the water rather than sliding over it, with faster smoother and much more seaworthy rides, especially offshore. In 1960, Hunt designed and Bertram built Moppie, a 31-foot boat based on a tender Hunt made himself, and used to win the famous Miami to Nassau Race. That became the Bertram 31, a version of which is still in production.

And, it wasn’t just Bertram. Hunt designed the original 13-foot Boston Whaler. in 1957. C. Raymond Hunt & Associates designed and engineered small boats, big boats, racers and trawlers for many builders, including Chris-Craft, Grady-White, Grand Banks and more than a few others.

So, next time you’re powering along offshore, thank Raymond Hunt. He’s why your boat is fast, smooth and stable.

Inventing the Outboard

Summer of 1905-ish, Ole and Mrs. Evinrude were picnicking on Lake Okauchee in Wisconsin.

Ole was sent for ice cream, and he rowed to shore, and bought the ice cream. By the time he got back to the family, the dessert had melted. Ole, the machinist and combustion-engine tinkerer, was a bit irritated. In 1907, he came up with a 1.5 horse transom-mounted gasoline powered outboard motor.

In 1911, he patented his invention, and in 1913 sold his interest to his partner in the Evinrude Motor Corporation. After five years off, he introduced a 3 hp aluminum model that weighed 48 pounds. He then joined forces in 1929 with his old company and Johnson Motor Company, and created the small boat revolution.

In 1911, he patented his invention, and in 1913 sold his interest to his partner in the Evinrude Motor Corporation. After five years off, he introduced a 3 hp aluminum model that weighed 48 pounds. He then joined forces in 1929 with his old company and Johnson Motor Company, and created the small boat revolution.

You can still buy a two-cylinder Evinrude – or one with up to 300 horsepower.

Boat Tow or No?

The obligation to render assistance is as old as the sea. You see another vessel in danger, and you go to help. Generally, there’s no excuse to not at least try, even if it’s a boat tow.

Reasons To Say NO

Even though boats seem to float and drift easily, they’re still heavy. That means some interesting loads on the towing boat. A few thousand pounds of boat at the the end of a lightweight tow line can get “western” in a hurry, even in flat water and no wind. Add some seas or a heavy chop and some real breeze and the tow can go bad quickly.

Most boats have relatively lightweight cleats, and most boaters don’t carry heavy lines – snapping lines and ripped out cleats aren’t helping your boat, or the boat you’re trying to help. It’s also likely that your power and props are just fine for motoring, fishing or skiing, and just aren’t suited for generating the torque necessary for towing a heavy load at lower speeds. Think about pulling another car on a wet road, spinning your tires the whole way. Probably not a good idea.

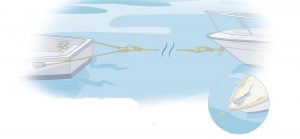

What About the Line?

A tow line should be eight or ten boat lengths (call it 250 to 300 feet) if you’re pulling a 30 foot boat. Most pleasure boats don’t carry line long enough or strong enough for serious towing. If you do have line, the worst to use is the standard three-strand nylon, since it has too much stretch, and tends to part explosively under load. Double-braided nylon is a better choice, but like any line that sinks, you’ll run the risk of fouling your props, if you allow too much slack. Your best bet is probably your anchor line, as it’s usually the longest and strongest line aboard.

Points and Cleats

Before you use that cleat or pad eye, first make sure it’s up to the task at hand. A too small cleat (even sometime a Forespar), a cheap cleat or poor installation can and will break, and can become a lethal missile if it snaps under load. Then, when you’re setting up the tow rig, use a “bridle” set forward with the length of each leg at least twice the width of your boat, distributing the tow load to both side of the boat, allowing you to maintain control, since a single line attached to the transom will truly degrade your steering. Then, adjust the tow line length so that your boat and the tow are in sync with the waves and troughs (remember that if you’re towing, the other boat probably doesn’t have brakes, so the tow tine may need to be slightly longer than you think).

A Knotty Issue

Knots used in towing are subject to heavy loads, so avoid knots that cinch tight. Cleat hitches and bowlines are ideal, as they won’t come untied under load, but are easy to release when required. And, no one stands in direct line with a loaded line (or should be dumb enough to straddle it), because if the line or cleat lets go, someone gets hurt.

Wait It Out

If there’s only one thing to take way here, it is to err on the side of caution. If you aren’t very sure of your ability to tow the other boat safely and effectively, don’t do it. The last thing the Coast Guard wants is two boats in trouble at the same place and time. Get on the radio and stand by for help, preferable a vessel with the equipment, know-how and insurance.

And thanks to the U.S. Coast Guard for their guidance, and not least, being ready to help us when and where it’s needed.

Aero Rig – Another Forespar Test

Bob Foresman, Forespar’s founder, never stopped innovating and testing sailing concepts – a company premise that continues today, 50 years later. From the original telescoping whisker poles made in the garage to today’s carbon fiber poles, furling systems and the rest of a catalog of boating products from the modern plant, the family continues to experiment, produce and sell new products.

A classic example is Fore Sail, the Foresman’s Catalina 400. Working with Catalina Yachts, Forespar developed Fore Sail as a test bed for a Forespar-built Aero Rig, with an eye toward a Catalina production model. While this ultimately proved impractical because of market conditions, an easy-to-sail (and single hand) 40-foot cruiser with a very different rig drew a lot of attention in the early 90’s. Shown here with Art Bandy, now the Forespar OEM Sales Manager, at the helm and strings tacking up the Newport Beach Lido Channel.

Sailing Downwind with Double Headsails

It sounds a lot more complicated than it is. All you need is:

• your usual genoa

• a second headsail

• a mast with two foresail halyards

• a whisker pole

Your destination is deep off the wind. The breeze is light to moderate, and you’d like to be moving faster, but either don’t have a spinnaker aboard, or just don’t want to wrestle with it. Wing-and-wing isn’t working because your course isn’t dead down wind, or you just don’t want to deal with the constant trimming. The usual solution is to come up on the wind, heat it up and get some boat speed, gybing your way to your mark. It’s more work, but it can get you there faster if you plan your gybes well.

Or go with two headsails.

Get the other sail on deck (it doesn’t matter if it’s your jib, another genoa, or in light air an appropriate sail). You can rig a new, separate sheet for the windward side, or even detach the lazy sheet from the working sail, as long as you remember to re-attach it before any gybes. Get the free halyard and new sheet hooked up with plenty of slack, and the new sail tacked on. Make sure the pole is ready to go. (We use a Forespar twist-lock pole, which adjusts to the right length for whatever sail we’re using).

Hoist the new windward sail, attach the pole as close to the sail clew as you can, adjust the pole length, and trim on. The rest is adjustment for the course and breeze. Then watch the boat go faster, especially in light air. You might even lower the mainsail, just go with the headsails.

You can go faster and deeper, with a lot less work. Ocean cruisers sometimes go hundreds of miles with a whisker pole – or even two headsails and two poles. Some races even allow double headsails (we’ve had great success in “inside” races using a light 155 genoa and our drifter). Try it on light days when you’ve got room to work, adjust and trim. It’s easy to do with two people, and requires a lot less muscle.

Go sailing. Have fun.

Mike Dwight

Steering Smaller Boats in Big Waves

First – what’s a big wave? Is it the 100-foot wave from The Perfect Storm”? Could it be the waves from a TV show called Bering Sea Gold, when they tell us there’s a storm, and it looks like all of 12 knots of breeze and two-foot chop?

The answer is yes. Any wave that makes you feel that you and your boat are in danger is a big wave. All that matters is that the waves are challenging you, and you’re nervous about handling them safely. There are some basic rules that can help:

- First -If conditions scare you, don’t go out. Getting macho can get you and your passengers in deep trouble. Getting back on Monday morning isn’t worth risking the safety and sanity of your crew.

The classic example is the trip back home from Catalina Island. You left the mainland early on Saturday, and it was flat with no wind, so you zoomed over (zoom speed is relative – maybe six knots from the Yanmar in the sailboat, and 30 knots from the twin Volvos in the cruiser). You leave for home on Sunday afternoon, and there 32 knots of breeze pushing some healthy wind waves along with a big swell rolling down the channel, and you’ve got 20 to 30 miles to go with that on your beam or under your quarter.

You are relatively inexperienced, but you’ll probably make it. You’ll beat up the boat, and scare the pants off your crew and yourself in the process. The crew may never get on the boat again. Or, you are experienced, and you’ll make it. You’ll wear yourself and the crew out, and the boat won’t be real happy either.

- Second- There’s no better teacher than experience, but try to gain that experience with an old hand aboard to help you learn. Often the difference between the emotion “We’re gonna die” and the comment “That was a big one” is usually perception and a twitch on the helm.

If you are next to the helm on one of those days, and the driver is calm and under control, it’s amazing how much you can learn just watching and listening. Then when you trade places and you’ve got the helm, a calm voice in your ear, coupled with the positive results, can help you learn a lot, and apply it at the same time. Then you gain the confidence to try it yourself.

- Third – Practice. When you go out, and it’s lumpy, take some time to drive the boat both uphill (into the wind and waves) and downhill (away from the wind and waves). Learn what make the boat feel and respond best under current conditions. You check the weather, then look out the harbor entrance. If you see other boats of your type in the vicinity, go out and play. Practice going into the wind, downwind, into the waves and away from them.

Going into the waves, while often scarier, is easier on the boat and the driver when you do it right.

Don’t worry about your specific destination – as long as you’re making up distance to the mark (technically VMG – Velocity Made Good), you’re doing well. If you steer at an angle somewhere between 20 ⁰ and 45⁰ off the face of the wave, the boat is a lot more comfortable, and is actually faster than heading straight into the sea. You don’t get the big flying spray, and you don’t get the big pounding crash, either. And, you’ll be under control.

Not steering at your mark seems counter-intuitive, but any racing sailor can tell you that it works.

That’s nice, you’re thinking, but at some point I have to make up for that angle away from the harbor mouth. You’re right. You do. If you’re paying attention, you’ll find a periodic flatter spot between waves that will allow you to make the turn (tack) without wrestling the boat over a bigger wave.

Heading downhill requires more touch, and more attention to your helm. The basic design of most powerboat hulls has a broad, usually flat, surface for the following wave to push on, along with a more or less square corner (the quarter). This means that when that big wave comes at the stern, it lifts the stern while pushing on that flat surface. The combination of shapes and forces make the stern want to go to the side, and the boat wanting to turn parallel to the wave’s face, tilting away from the rising wave. This can make for some interesting or even dangerous moments. Sailboats do the same, but with a less exaggerated motion.

With some practice, you can learn to anticipate your boat’s tendencies, and start steering up the face and down the backs of oncoming waves, into the direction that swinging stern takes (It’s called “Yaw”) on following seas.

- Fourth – Watch Your Speed. If you pay close attention to your boat speed relative to the waves, and adjust accordingly, you’ll find the sweet spot. Wind waves are usually moving at speeds from 13 to 18 knots, so you want to work around that basic datum. If you’re steering into the waves, and in a hurry with 15 knots of boat speed, you’re meeting big walls of water at 30 knots (just under 35 mph). The air is getting under your hull, and you’re flying a bit. That is a lot of energy your boat has to absorb when you hit the next wave. A lot of wear and tear on the boat and the bodies aboard.

When steering off the wind, some of the math works for you. If the waves are moving at 13 knots, and you throttle back to about 13 knots, keeping the bow down enough to increase your waterline (hence control and comfort), you’ll find that steering the boat and managing the course is a great deal easier. The waves are coming at you a lot slower, and you have much more time to make your adjustments to steer a comfortable and productive course. With some practice, you’ll find yourself actually surfing the boat.

Think safe, learn well, practice and slow down. Your boat, your backs and your butts will be much happier.

Mike Dwight

FAQ of the Week

Q: What is required to install my Hoyt Boom System?

A: When installing the Hoyt boom, a backing plate is recommended for structural support, which Forespar® does not manufacture. The backing plate must be the same diameter as the pedestal and should be of sufficient thickness to help spread the fastener load. The backing plate can be made of teak, aluminum, stainless steel or hard plastic such as ABS or Nylon. The pedestal can be installed more than 10 feet aft of the J length. If this is done, your jib will most likely need to be re-cut. Make sure the Hoyt boom is installed before you have a sail maker adjust your jib.

The boom needs to be installed so that the pedestal is level. Forespar® sells shims that adjust the pedestal up to a 6o angle. If your deck is angled more than 6o you will have to have custom shims made. It is recommended that a professional rigger install your Hoyt boom to maintain structural integrity. Detailed instructions for installation can be found at http://www.Forespar.com/products/sail-hoyt-jib-boom-system.shtml.

If you have any further questions or need replacement parts, please contact us at sales@forespar.com.

FAQ of the Week

Q: What size Hoyt Boom should I buy for my boat?

A: Deciding what size Hoyt boom to buy is dependent on overall boat length and J dimensions. Model 250 is recommended for boat lengths 25’-29’, Model 300 is for boats 30’-35’ and Model 350 is for boats 35’-42’. More details about choosing the right size can be found here Hoyt Jib Boom.

If you have any further questions or need replacement parts, please contact us at sales@forespar.com.