Forespar's Point of View

Blogging About Life on the WaterCategory Archives: Uncategorized

Further: Kids on the Water

After the 100-foot Comanche crushed the Newport Bermuda Race record by almost five hours, finishing June 19, it has taken the next boat over two more days to reach Bermuda. While Comanche’s finish position was predicted, few could say the same about the runner-up.

High Noon, at 41 feet, is fully 59 feet shorter than Comanche and tens of feet shorter than many other of the 142 starters. Yet High Noon was the second boat to finish , and did so with a 10-person crew, seven of which are teenagers between ages 15 and 18.

This is all about old/new ideas in training young sailors. For decades they sailed only small boats. Enter Peter Becker, who sails out of American Yacht Cub, in Rye, New York. He was an eager 15-year-old when he sailed his first Newport Bermuda Race. “I was the kid on the boat, up on the bow changing sails,” he recalls. Since then he’s done 16 more Bermuda Races and a race from New York to Barcelona, Spain.

Four years ago his teenage children were getting interested in ocean racing, and he came up with a new approach: a unique training program at his club that came to be called the Young American Junior Big Boat Sailing Team.

He put youngsters in a J/105 racing in local regattas under the his tutelage and that of other big-boat sailors.

From there the youth sailors crewed on short, then longer ocean races, even delivering boats home after the races. It worked so well that for the 2016 Newport Bermuda Race, the US Merchant Marine Academy Sailing Foundation loaned High Noon to his program.

The results are apparent. You need crew? Draft juniors. They’re often as good or better than you are – and a whole lot more agile.

Get the Kids on the Water!

It’s about time.

US Sailing and others are pushing to get kids and young people out on the water sailing. Not necessarily racing, but sailing.

My suggestions may be facile, but: (a) Start them early, and (b) Keep them involved in the process when they’re out there – no passengers.

Our primary YC offers one of the finer Juniors’ programs on the West Coast. While we have some superb racers in the Junior ranks, many race in the Harbor for the competitive fun of it, many sail just for the fun. We start Juniors in the “Starfish” program at about age five, when we can. They’re more at summer camp than on the water, but they are exposed to fun part of boating, with a dose of responsibility. that can then graduate to on the water, first sailing with coaches, then Sabots (racing if they want to), then Optis, then Lidos for fun, or 420’s to race, etc.

And, while we’re at it, there are a number of racing skippers who make sure that competent (meaning safe) juniors, mostly adolescents, crew on their boats for local PHRF races, and even on some of the distances races – again, no passengers. One skipper sailed the Newport-Ensenada race with eight kids and four adults, finishing fifth in a class of 15. All the juniors on that crew are sailing. Five are still racing , three on a national level, and three sail for fun.

The end result has been sailors who started in the Club at five, with about half of a twenty-year program philosophy still sailing (and that doesn’t count the power boaters). That means BCYC Junior sailing program has produced about 200 sailors still on the water, and more than that overall in recreational boaters.

That also means a pretty good crew pool for those of us who race a lot.

Make it fun, and they will come.

Bloopers

Ocean racing is just about to become more colorful – again!

The new ORR rules are allowing bloopers on non-sprit boats (with some restrictions). For sailors who don’t remember, look at the picture, and check out the big sail tacked to the port bow.

Look at the wake, and the waves, and realize just how deep and fast they’re sailing. Pole back a bit, ease the main a bit, and trim on the the blooper and that boat is still launched – even dead down wind. In light and moderate air, you’ve got a big downwind sail you trim with the halyard. You’ll want a racing crew with someone who either has or can develop a different set of trimming skill, but you’ll make up for it with VMG and boat speed. That blooper helps narrow the gap between an older boat and the sprit boats.

We’ll see them this year on the ocean races such as Bermuda, Transpac and Mackinac.

The ORR rule limits blooper use by treating the blooper as headsail (no pole), and within the number of sails the boat is allowed to carry. It has to be attached to the bow, and there are restraints on the boats allowed to fly them, as in basic design from before 1986. And couple of cautions: Think oscillations. Think about a little too much breeze and an interesting round up or crash jibe.

On the other hand, think speed.

Mike Dwight

Rights of Others on the Water

Not everyone shares your taste in music. Or sports. Or boats. Or recreation. Or wakes. Or engine noise. Or even beverages. Even if they do, they probably don’t want to share right now.

It’s easy to get totally focused on what you’re doing, even in a shared environment. Let’s face it: when you’re cranking along at 25 knots, your attention is on making sure you don’t hit anything solid, and the exhilaration of speed on the water. You’re not looking back at your wake, and seeing how much the swimmers, paddle boarders and kayakers appreciate it. Or how much the waterfront folks enjoy watching their watercraft bang on the dock. And the people out for a quiet day fishing really want to compliment you on your speakers and how loud your motors are.

They’re just as happy as you are when you’ve just nestled in to bed after a long day on the water, and someone drops anchor next to you, invites friends, fires up the generator, plugs in the blender and the music, and parties down until the crack of dawn.

They’re just as happy as you are when you’ve just nestled in to bed after a long day on the water, and someone drops anchor next to you, invites friends, fires up the generator, plugs in the blender and the music, and parties down until the crack of dawn.

The long and the short of it is that you ARE in a SHARED environment.

Even the gray whales in Bahia Todos Santos shy away from noisy boaters, and bass in the lakes don’t really flock to rock and roll.

Respect the rights of others. Show some consideration for the people around you.When you’re at the launch ramp or the dock, be quick and make room for the next boat. Respect the private property along the shore. Make sure you have permission to go ashore, use the dock, or cross their land. And so on….

Remember, the other folks in or on the water have the same rights you do. And, just like you, all they want is a good day on the ocean, lake or river.

~ Mike Dwight

Check Your Chain Plates

When was the last time you inspected your chainplates? Shrouds and tangs, of course, because they’re easy to see, but the chainplates themselves. If you take the time, and carefully inspect all parts of the rig, you can prevent failures – and losing the rig is at best a bad thing.

Many boat owners, especially those with newer boats, aren’t real sure what a chainplate is, or how essential to the rig they are. Since they provide the foundation of the rig at the base of the shrouds and stays, they’re often masked behind surfaces and seat backs.

They can be hidden or right out in view, as in these pictures from Ericson Yachts

Regardless, they bear huge loads, and are a common point of failure. Remember, stainless is not permanent, and is subject to metal fatigue and corrosion, especially after about ten years. At that point, it becomes a very good idea to inspect the chainplates, fore and aft, side to side, when you’re planning a cruise, and especially if you sail in heavy air or seas. We’ve all “replaced” our standing rigging without a thought to the chainplates.

Look at the photo above. When this happens, your rig gets very unhappy, and so will you. Get down below and take a good hard look at those plates and straps. Or better yet, ask your rigger or a surveyor for an inspection. The worst thing that can happen is nothing, and that’s good.

Mike Dwight

Sailing Downwind with Double Headsails

It sounds a lot more complicated than it is. All you need is:

• your usual genoa

• a second headsail

• a mast with two foresail halyards

• a whisker pole

Your destination is deep off the wind. The breeze is light to moderate, and you’d like to be moving faster, but either don’t have a spinnaker aboard, or just don’t want to wrestle with it. Wing-and-wing isn’t working because your course isn’t dead down wind, or you just don’t want to deal with the constant trimming. The usual solution is to come up on the wind, heat it up and get some boat speed, gybing your way to your mark. It’s more work, but it can get you there faster if you plan your gybes well.

Or go with two headsails.

Get the other sail on deck (it doesn’t matter if it’s your jib, another genoa, or in light air an appropriate sail). You can rig a new, separate sheet for the windward side, or even detach the lazy sheet from the working sail, as long as you remember to re-attach it before any gybes. Get the free halyard and new sheet hooked up with plenty of slack, and the new sail tacked on. Make sure the pole is ready to go. (We use a Forespar twist-lock pole, which adjusts to the right length for whatever sail we’re using).

Hoist the new windward sail, attach the pole as close to the sail clew as you can, adjust the pole length, and trim on. The rest is adjustment for the course and breeze. Then watch the boat go faster, especially in light air. You might even lower the mainsail, just go with the headsails.

You can go faster and deeper, with a lot less work. Ocean cruisers sometimes go hundreds of miles with a whisker pole – or even two headsails and two poles. Some races even allow double headsails (we’ve had great success in “inside” races using a light 155 genoa and our drifter). Try it on light days when you’ve got room to work, adjust and trim. It’s easy to do with two people, and requires a lot less muscle.

Go sailing. Have fun.

Mike Dwight

Bad Water in Rio

Rio Olympic Water Badly Polluted…Even Far Offshore

In July the AP reported that its first round of ocean water tests showed disease-causing viruses directly linked to human sewage at levels to be considered highly alarming in the U.S. or Europe. Experts said athletes were competing in the viral equivalent of raw sewage and exposure to dangerous health risks almost certain.

The story gets worse – the pollution and the IOC’s passive reaction has caused World Sailing’s president to resign!

In August, after pre-Olympic rowing and sailing events in Rio led to illnesses among athletes nearly double the acceptable limit in the U.S. for swimmers in recreational waters, sports officials pledged that the waters were safe for competition in next year’s games. Since August water testing reveals more widely contamination than previously known. The number of viruses found over a kilometer from the shore in Guanabara Bay, where sailors compete at high speeds and get utterly drenched, are equal to those found along shorelines closer to sewage sources.

The Rio 2016 Olympic organizing committee said that “the health and safety of athletes is always a top priority and there is no doubt that water within the field of play meets the relevant standards.” AP’s testing in Rio, where the water often falls within safe fecal bacteria levels, but shows levels of viruses akin to raw sewage. Many of the testing points show spikes in bacterial contamination — especially in the Olympic lagoon and in the marina where sailors launch crafts. Rio’s waterways, like those of many developing nations, are contaminated because most of the city’s sewage is not treated and massive amounts of it flow straight into Guanabara Bay.

Rio won the right to host the Olympics based on a lengthy bid document that promised to clean up the city’s scenic waterways by improving sewage sanitation; Brazilian officials now acknowledge that won’t happen.

Athletes in Rio test events have tried many treatments to avoid falling ill, including bleaching rowing oars, hosing off their bodies the second they finish competing, and preemptively taking antibiotics — which have no effect on viruses. In August, athletes at a competition fell ill; The World Rowing Federation reported that 6.7 percent of 567 rowers got sick at a junior championships event in Rio. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s maximum illness rate for swimming is 3.6 percent — and many experts say that is too high.

Water quality experts say a virus count hitting 1,000 per liter in the U.S. or Europe would cause extreme alarm, leading in many cases to beach closures. Recent viral levels were all 30,000 times higher than the U.S. or European highly alarming levels at every of AP’s new offshore sampling sites: at a point 600 meters (yards) offshore and within the Sugarloaf sailing race course; at 1,300 meters (yards) offshore within the Naval School sailing circuit; and at a spot inside the Olympic lagoon where rowing lanes are located, about 200 meters (yards) from shore.

In September tests at the Naval School race course and offshore lagoon points, the water tested positive for enterovirus, a major cause of respiratory illness, gastrointestinal ailments and, less often, serious heart and brain inflammation.

Risk assessment experts say that the sheer number of pathogens in Rio’s waters means the risk to human health is unacceptable. Rio de Janeiro state authorities promised to complete sewerage infrastructure near the Marina da Gloria by the end of this year and are making progress. Authorities say Olympic venues will then be safe.

But the high levels of sewage-linked pathogens found in the offshore sailing courses pollution come from dozens of rivers that crisscross metropolitan Rio and dump millions of liters of raw sewage into the bay each day. By the government’s own estimate, just half of the city’s wastewater flowing into the bay is treated.

Sailors are concerned as are other venue participants. One American, himself a winner of two gold medals and one bronze swimming medals at the 1992 Barcelona Games, said if his daughter were a contender in Rio’s open-water swimming competition, he would tell her not to compete. “A gold medal is not worth jeopardizing your health, and it doesn’t appear at this point that the athletes are being considered first.” RIO DE JANEIRO (AP-Brad Brooks). This is a dilemma Olympians don’t need to be worried about. POV Pat Dwight

Respected Sailing World Spokesperson John Kretschmer Comments on Forespar’s Whisker Poles

“My Forespar 50/50 Whisker Pole is a workhorse, no other piece of equipment on Quetzal is more useful for efficient off the wind sailing. I would not go to sea without it.”

Process: Lubricating Marelon Valves with the Boat Hauled

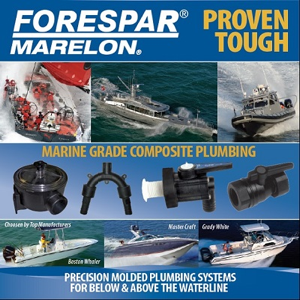

Marelon® is a proprietary formulation of polymer composite compounds used to produce superior marine-grade products for above and below the waterline.

Created specifically for precision molded plumbing systems, Marelon® offers complete freedom from corrosion and the ravages of electrolysis.

At least half the weight of their bronze counterparts, Marelon® plumbing components provide strength, light weight and internationally approved underwater systems that provide years of trouble-free, corrosion-free and electrolysis-free use.

Routine lubrication of marine seacocks (Marelon®, bronze or stainless steel on all valves) in any boat is vital for their prolonged life and ease of operation.

If ball seals are allowed to dry out, you will experience increased drag caused by marine growth which scores the seals and ultimately leads to leaks, difficulty in operation and/or blockage – potentially harming the equipment they serve.

Lubricating a Marelon® Valve with the Boat Hauled

- Open valve, to drain any residual water, then close valve and remove the hose from the TOP of the hose line connection. On drains or other easily accessible thru-hull/valve hose lines, you may not need to remove the hose. During this step, it’s wise to check for worn hose and rusty hose clamps.

- Outside of the hull have a second person use a bucket to catch the run-off MareLube™ Liquid as the valve is opened and closed. Catch the lube as it runs through the line for re-use on the next line. Be sure you are under the correct thru-hull before starting!

- Repeat the process on all the thru-hull/valve hose lines. MareLube™ Liquid is not harmful to the environment so don’t worry if some splashes.

- This process requires two people.

This procedure is easy and should be done at the beginning of the dry storage season and again before launch. The MareLube™ liquid will leave a PTFE coating throughout the line and help keep hoses clean.

Accessibility to all valves is important and essential for the safety of the vessel should disaster strike. Any marine valve regardless of material, if not activated periodically, will seize, have marine growth build up inside and be rendered inoperable due to neglect.

It is strongly recommended to be particularly watchful of those hard-to-reach valves and find a way to reach them, since regular activating, servicing or closing them in an emergency is important.

Forespar® provides Marelon® plumbing systems to the world’s top boat builders and continues to develop modern alternatives to age old heavy bronze fittings. We are the only manufacturer to offer motorized Marelon® seacocks (ROV systems) that meet and exceed all Marine U.L., ABYC and ISO standards.

Forespar® has products to answer every boaters needs! To learn more, visit http://www.forespar.com/what-is-marelon.shtml.

POV Pat Dwight

A Special Event for Special Sailors

2015 Blind National Sailing Championship Event Scheduled Sept. 12-13 in Newport RI

While the 2015 Blind National Sailing Championship won’t take place until September in Newport RI, last year’s 2014 blind sailing championship regatta was a fabulous event. The 2014 regatta provided two days of great racing between Rose and Goat islands with fierce competition between seven teams over 12 races.

Congratulations to Duane Farrar, Solomon Marini, Denis Bell and Amy Bower for winning and being named the 2014 Blind National Champions.

Sail Newport will be hosting the 2015 Blind National Championships this coming September. For details contact Sail Newport’s Regatta Manager

Pat Dwight

~Forespar POV