Forespar's Point of View

Blogging About Life on the WaterCategory Archives: General Content

Forespar Marelon Plumbing Honored

We are very honored and excited to have been named the 2015 recipient of the Fisheries Supply InNEWvation award in the Plumbing category! Pictured are our own designers John Dean and Art Bandy with the award-winning ClearView End Fittings. Forespar’s composite boat plumbing features the full line of Marelon, from seals and fitting to a full array of valves.

Mike Dwight

Aero Rig – Another Forespar Test

Bob Foresman, Forespar’s founder, never stopped innovating and testing sailing concepts – a company premise that continues today, 50 years later. From the original telescoping whisker poles made in the garage to today’s carbon fiber poles, furling systems and the rest of a catalog of boating products from the modern plant, the family continues to experiment, produce and sell new products.

A classic example is Fore Sail, the Foresman’s Catalina 400. Working with Catalina Yachts, Forespar developed Fore Sail as a test bed for a Forespar-built Aero Rig, with an eye toward a Catalina production model. While this ultimately proved impractical because of market conditions, an easy-to-sail (and single hand) 40-foot cruiser with a very different rig drew a lot of attention in the early 90’s. Shown here with Art Bandy, now the Forespar OEM Sales Manager, at the helm and strings tacking up the Newport Beach Lido Channel.

Steering Smaller Boats in Big Waves

First – what’s a big wave? Is it the 100-foot wave from The Perfect Storm”? Could it be the waves from a TV show called Bering Sea Gold, when they tell us there’s a storm, and it looks like all of 12 knots of breeze and two-foot chop?

The answer is yes. Any wave that makes you feel that you and your boat are in danger is a big wave. All that matters is that the waves are challenging you, and you’re nervous about handling them safely. There are some basic rules that can help:

- First -If conditions scare you, don’t go out. Getting macho can get you and your passengers in deep trouble. Getting back on Monday morning isn’t worth risking the safety and sanity of your crew.

The classic example is the trip back home from Catalina Island. You left the mainland early on Saturday, and it was flat with no wind, so you zoomed over (zoom speed is relative – maybe six knots from the Yanmar in the sailboat, and 30 knots from the twin Volvos in the cruiser). You leave for home on Sunday afternoon, and there 32 knots of breeze pushing some healthy wind waves along with a big swell rolling down the channel, and you’ve got 20 to 30 miles to go with that on your beam or under your quarter.

You are relatively inexperienced, but you’ll probably make it. You’ll beat up the boat, and scare the pants off your crew and yourself in the process. The crew may never get on the boat again. Or, you are experienced, and you’ll make it. You’ll wear yourself and the crew out, and the boat won’t be real happy either.

- Second- There’s no better teacher than experience, but try to gain that experience with an old hand aboard to help you learn. Often the difference between the emotion “We’re gonna die” and the comment “That was a big one” is usually perception and a twitch on the helm.

If you are next to the helm on one of those days, and the driver is calm and under control, it’s amazing how much you can learn just watching and listening. Then when you trade places and you’ve got the helm, a calm voice in your ear, coupled with the positive results, can help you learn a lot, and apply it at the same time. Then you gain the confidence to try it yourself.

- Third – Practice. When you go out, and it’s lumpy, take some time to drive the boat both uphill (into the wind and waves) and downhill (away from the wind and waves). Learn what make the boat feel and respond best under current conditions. You check the weather, then look out the harbor entrance. If you see other boats of your type in the vicinity, go out and play. Practice going into the wind, downwind, into the waves and away from them.

Going into the waves, while often scarier, is easier on the boat and the driver when you do it right.

Don’t worry about your specific destination – as long as you’re making up distance to the mark (technically VMG – Velocity Made Good), you’re doing well. If you steer at an angle somewhere between 20 ⁰ and 45⁰ off the face of the wave, the boat is a lot more comfortable, and is actually faster than heading straight into the sea. You don’t get the big flying spray, and you don’t get the big pounding crash, either. And, you’ll be under control.

Not steering at your mark seems counter-intuitive, but any racing sailor can tell you that it works.

That’s nice, you’re thinking, but at some point I have to make up for that angle away from the harbor mouth. You’re right. You do. If you’re paying attention, you’ll find a periodic flatter spot between waves that will allow you to make the turn (tack) without wrestling the boat over a bigger wave.

Heading downhill requires more touch, and more attention to your helm. The basic design of most powerboat hulls has a broad, usually flat, surface for the following wave to push on, along with a more or less square corner (the quarter). This means that when that big wave comes at the stern, it lifts the stern while pushing on that flat surface. The combination of shapes and forces make the stern want to go to the side, and the boat wanting to turn parallel to the wave’s face, tilting away from the rising wave. This can make for some interesting or even dangerous moments. Sailboats do the same, but with a less exaggerated motion.

With some practice, you can learn to anticipate your boat’s tendencies, and start steering up the face and down the backs of oncoming waves, into the direction that swinging stern takes (It’s called “Yaw”) on following seas.

- Fourth – Watch Your Speed. If you pay close attention to your boat speed relative to the waves, and adjust accordingly, you’ll find the sweet spot. Wind waves are usually moving at speeds from 13 to 18 knots, so you want to work around that basic datum. If you’re steering into the waves, and in a hurry with 15 knots of boat speed, you’re meeting big walls of water at 30 knots (just under 35 mph). The air is getting under your hull, and you’re flying a bit. That is a lot of energy your boat has to absorb when you hit the next wave. A lot of wear and tear on the boat and the bodies aboard.

When steering off the wind, some of the math works for you. If the waves are moving at 13 knots, and you throttle back to about 13 knots, keeping the bow down enough to increase your waterline (hence control and comfort), you’ll find that steering the boat and managing the course is a great deal easier. The waves are coming at you a lot slower, and you have much more time to make your adjustments to steer a comfortable and productive course. With some practice, you’ll find yourself actually surfing the boat.

Think safe, learn well, practice and slow down. Your boat, your backs and your butts will be much happier.

Mike Dwight

Boat Show Season Is Here…How To Pick Your Boat!

For boaters who have the courage to go “boat hunting” or just to “take a look” you will likely wind up wanting to buy at least three that you find.

Making the right decision about your selection process can be simplified if you use these seven hints during the journey:

- You start comparing all other boats to her. It’s okay to admire the also-rans, but usually that just proves which boat owns your whole heart.

- You gasp. Out loud. With the one, this will happen repeatedly, to the point that strangers may ask if you’re having an asthma attack.

- You can’t stop touching her. If you hear yourself saying something like, “The texture of these teak handrails is just absolute perfection,” it’s a sign that you’re going over the edge.

- Her smell lingers on your mind. Whether it’s the chlorine from the hot tub or the diesel from the engine room, somehow it all smells like a sweet French fragrance to you.

- The helm seat fits you perfectly. Every gauge is at eye level, every control is within easy reach, every inch of your rear-end is cushioned and every dollar you have will soon belong to the builder.

- You stand, fully clothed, in the master cabin shower. We all know you’re dreaming about adding a steam feature and the spaciousness. You can’t hide it at this point.

- Your better half gives you the nod. If your spouse says yes, make the deposit without delay. You’ll never get another chance this good to spend money on the mistress of your dreams.

* Points provided by Yachting Magazine

~ Forespar Point of View Team

Rock and Roll

There’s a place for rock and roll and it’s not on an anchored boat.

Salt water boaters often find themselves anchored or on a mooring. There’s a swell, a surge from the swell or just enough breeze to create some waves, all just enough to rock the boat. That rock can be strong enough to be uncomfortable. It is hard to sleep with a grip on the mattress, and an evening on the deck or in the cockpit isn’t very comfortable.

A flopper stopper is the solution. I’ve tried several types over the years, and settled on one that works across the board – the Roll-X™ from Forespar. The same system has dampened the roll quite well on my power boats (a Grand Banks 42 and a 28’ Wellcraft) and my sail boats (a Baltic 52, and a Soverel 33), as well as other vessels.

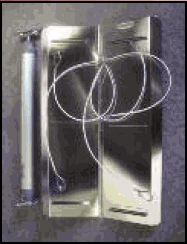

The Roll-X stabilizer consists of two stainless plates, about 12.5 by 40 inches, hinged together, and supported by a single line attached to a basic harness. It works simply. On the down roll, the unit folds together on the hinges, and drops deeper. On the up roll it unfolds, creating about seven square feet of resistance – sufficient to dampen a dramatic roll, completely quash a smaller wake or wind wave. And, the Roll-X has winglets to minimize the “skate” fore and aft while down, making the ride even more.

Roll-X stabilizer is most efficient when used with a pole to increase the leverage (one comes with the kit). You can see how on the trawler below.

Many sailors use the poles they’ve already got – spinnaker pole, a heavy whisker pole and often the boom. Swing it out on a halyard or topping lift, and couple of lines for guys and the crew is going enjoy a lot more stable time at anchor.

Candidly, the Roll-X stabilizer works pretty well as a flopper stopper with no poles, although using two (one on each side) helps make up for the lack of leverage. They are simply lowered over the side, down six or eight feet, and made fast to the cleats nearest the beam of the boat. Yes, we were in a hurry, or just too lazy to rig properly. They do work better poled out, and you must be sure to hoist the stabilizers in before weighing anchor and sailing away.

You can be sure that you’ll be well rested because you’ve experienced a lot less rock and roll.

Mike Dwight

Long Beach to Dana Point Race

Attention Southern California PHRF racers! It’s time – once again – for the Long Beach to Dana Point Race. This 39 mile course for PHRF Classes and a shorter course for the Cruising Class is lots of fun for you and your crew! A great race to celebrate the end of summer with your family.

Baby (Seal) on Board

Check out this incredible video of a baby seal climbing on this surfer’s board!

The Charles W. Morgan Returns Home!

“Taking this American icon, the oldest surviving commercial ship in the country, out on her 38th voyage was a landmark achievement for Mystic Seaport,” said seaport president Steve White. “We truly accomplished our mission to celebrate our nation’s shared maritime heritage.” (NBC)

The Morgan embarked on its very first voyage in the year 1841. America’s oldest commercial whaling ship, the Morgan played a vital role in American maritime history. On August 6th, she returned home to Mystic Seaport in Connecticut to a warm welcome celebration.

Old Ship Found Buried Under Old Twin Towers

The recently reported story making headlines discusses the discovery of an old ship which was found at the excavation site of the 9/11 Twin Towers. Although the discovery was made four years ago, scientists have recently reached an explanation for the mysterious find.

Discovered 22 feet below street level, the Hudson River Sloop was constructed from what scientists believe is the same white oak tree wood that was used to build Independence Hall in Philadelphia. The rings in the wood suggest that it was cut from the white oak trees in 1773, just two years before the Revolutionary War.

Photos courtesy of Dailymail.co.uk

Want a Ride on the Prestige Lexington Yacht? Get in Line!

For products you can use on YOUR yacht, check out www.forespar.com!