Forespar's Point of View

Blogging About Life on the WaterCategory Archives: General Content

Steering in Big Waves

What’s a big wave? Is it the 100-foot wave from The Perfect Storm”? Could it be the waves from a TV show called Bering Sea Gold, when they tell us there’s a storm, and it looks like all of 12 knots of breeze and two-foot chop?

The answer is yes. Any wave that makes you feel that you and your boat are in danger is a big wave. All that matters is that the waves are challenging you, and you’re nervous about handling them safely. There are some basic rules that can help:

- First -If conditions scare you, don’t go out. Getting macho can get you and your passengers in deep trouble. Getting back on Monday morning isn’t worth risking the safety and sanity of your crew.

The classic example is the trip back home from Catalina Island. You left the mainland early on Saturday, and it was flat with no wind, so you zoomed over (zoom speed is relative – maybe six knots from the Yanmar in the sailboat, and 25 knots from the twin Volvos in the cruiser). You leave for home on Sunday afternoon, and there 32 knots of breeze pushing some healthy wind waves along with a big swell rolling down the channel, and you’ve got 26 to 45 miles to go with that on your beam or under your quarter.

You are relatively inexperienced, but you’ll probably make it. You’ll beat up the boat, and scare the pants off your crew and yourself in the process. The crew may never get on the boat again. Or, you are experienced, and you’ll make it. You’ll wear yourself and the crew out, and the boat won’t be real happy either.

- Second- There’s no better teacher than experience, but try to gain that experience with an old hand aboard to help you learn. Often the difference between the emotion “We’re gonna die” and the comment “That was a big one” is usually perception and a twitch on the helm.

If you are next to the helm on one of those days, and the driver is calm and under control, it’s amazing how much you can learn just watching and listening. Then when you trade places and you’ve got the helm, have a calm voice in your ear, coupled with the positive results, can help you learn a lot, and apply it at the same time. Then you gain the confidence to try it yourself.

- Third – Practice. When you go out, and it’s lumpy, take some time to drive the boat both uphill (into the wind and waves) and downhill (away from the wind and waves). Learn what makes the boat feel and respond best under current conditions. You check the weather, then look out the harbor entrance. If you see other boats of your type in the vicinity, go out and play. Practice going into the wind, downwind, into the waves and away from them.

Going into the waves, while often scarier, is easier on the boat and the driver when you do it right.

Don’t worry about your specific destination – as long as you’re making up distance to the mark (technically VMG – Velocity Made Good), you’re doing well. If you steer at an angle somewhere between 20 ⁰ and 45⁰ off the face of the wave, the boat is a lot more comfortable, and is actually faster than heading straight into the sea. You don’t get the big flying spray, and you don’t get the big pounding crash, either. And, you’ll be under control.

Not steering at your mark seems counter-intuitive, but any racing sailor can tell you that it works.

That’s nice, you’re thinking, but at some point I have to make up for that angle away from the harbor mouth. You’re right. You do. If you’re paying attention, you’ll find a periodic flatter spot between waves that will allow you to make the turn (tack) without wrestling the boat over a bigger wave.

Heading downhill requires more touch, and more attention to your helm. The basic design of most powerboat hulls has a broad, usually flat, surface for the following wave to push on, along with a more or less square corner (the quarter). This means that when that big wave comes at the stern, it lifts the stern while pushing on that flat surface. The combination of shapes and forces make the stern want to go to the side, and the boat wanting to turn parallel to the wave’s face, tilting away from the rising wave. This can make for some interesting or even dangerous moments. Sailboats do the same, but with a less exaggerated motion.

With some practice, you can learn to anticipate your boat’s tendencies, and start steering up the face and down the backs of oncoming waves, into the direction that swinging stern takes (It’s called “Yaw”) on following seas.

- Fourth – Watch Your Speed. If you pay close attention to your boat speed relative to the waves, and adjust accordingly, you’ll find the sweet spot. Wind waves are usually moving at speeds from 13 to 18 knots, so you want to work around that basic datum. If you’re steering into the waves, and in a hurry with 15 knots of boat speed, you’re meeting big walls of water at 30 knots (just under 35 mph). The air is getting under your hull, and you’re flying a bit. That is a lot of energy your boat has to absorb when you hit the next wave. Saves a lot of wear and tear on the boat and the bodies aboard.

- Fifth – Steer easy. Remember, the rudder is turning the stern, not the bow, so you’re always just a beat ahead of the boat’s motion. That means you can be making exaggerated corrections, larger and larger turns, out of synch with the waves. That leads to more bounce, more roll, and frayed nerves. Usually, it’s just slow the boat speed a bit, slow the steering a bit, and get into the rhythm.

When steering off the wind, some of the math works for you. If the waves are moving at 13 knots, and you throttle back to about 13 knots, keeping the bow down enough to increase your waterline (hence control and comfort), you’ll find that steering the boat and managing the course is a great deal easier. The waves are coming at you a lot slower, and you have much more time to make your adjustments to steer a comfortable and productive course. With some practice, you’ll find yourself actually surfing the boat on the swell.

Take it easy. Think safe, learn well, practice and just slow down. Your boat, your back and your crew will be much happier.

Hunt Made Us Go Faster

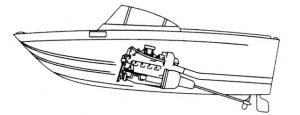

C. Raymond Hunt  had one of the most significant impacts on modern boating, right up there with Ole Evinrude and Olin Stephens.

had one of the most significant impacts on modern boating, right up there with Ole Evinrude and Olin Stephens.

Hunt was the naval architect credited with designing the first deep-vee hull(s). He started working with sailboat and lobster boat designs in the 1930’s in Massachusetts, and experimenting with deeper deadrise hulls for powerboats in the 40’s. That led to the revolution in powerboats, with deep-vee designs creating boats that knife through the water rather than sliding over it, with faster smoother and much more seaworthy rides, especially offshore. In 1960, Hunt designed and Bertram built Moppie, a 31-foot boat based on a tender Hunt made himself, and used to win the famous Miami to Nassau Race. That became the Bertram 31, a version of which is still in production.

And, it wasn’t just Bertram. Hunt designed the original 13-foot Boston Whaler. in 1957. C. Raymond Hunt & Associates designed and engineered small boats, big boats, racers and trawlers for many builders, including Chris-Craft, Grady-White, Grand Banks and more than a few others.

So, next time you’re powering along offshore, thank Raymond Hunt. He’s why your boat is fast, smooth and stable.

Inventing the Outboard

Summer of 1905-ish, Ole and Mrs. Evinrude were picnicking on Lake Okauchee in Wisconsin.

Ole was sent for ice cream, and he rowed to shore, and bought the ice cream. By the time he got back to the family, the dessert had melted. Ole, the machinist and combustion-engine tinkerer, was a bit irritated. In 1907, he came up with a 1.5 horse transom-mounted gasoline powered outboard motor.

In 1911, he patented his invention, and in 1913 sold his interest to his partner in the Evinrude Motor Corporation. After five years off, he introduced a 3 hp aluminum model that weighed 48 pounds. He then joined forces in 1929 with his old company and Johnson Motor Company, and created the small boat revolution.

In 1911, he patented his invention, and in 1913 sold his interest to his partner in the Evinrude Motor Corporation. After five years off, he introduced a 3 hp aluminum model that weighed 48 pounds. He then joined forces in 1929 with his old company and Johnson Motor Company, and created the small boat revolution.

You can still buy a two-cylinder Evinrude – or one with up to 300 horsepower.

Anchoring Etiquette

Boaters usual ly know that anchoring in the channel or the fairway is not only a bad idea, but illegal. and unsafe.

ly know that anchoring in the channel or the fairway is not only a bad idea, but illegal. and unsafe.

Most of the time, it’s not that simple. How’s your anchoring etiquette?

The First Boat In Sets The Rule

You motor around the point into your favorite cove, and you see another boat already anchored, swinging off a single hook. Etiquette dictates that you do the same, dropping your single hook on a spot that will keep you clear of the other boat when wind and tide change. If it’s relatively shallow, some of us even buoy the anchor, so others will know where it is (a spare fender and a few feet of paracord will usually do).

Then, how do you compute the swing radius – yours and the other boat’s? You can always do the math of a right triangle using water depth and scope to get the unknown – the distance from the boat to the anchor, But, assumptions of a 7:1 scope aside, that swing radius is going to change. Tides rise and fall, wind and currents change, and different boats react differently to those changes.

Keel sailboats react faster to current shifts, and later to wind, while power cruisers, especially those with two or three deck levels, react to wind faster than current. To make it even more fun, boats using all-chain rodes usually lay to scope of 3:1, as opposed to the 7:1 typical of boats with a rope rode. And funner yet, the other skipper may have more rode out than you thought, and you’ve swung to lie right above his hook, of course just when he/she is trying to leave – no big deal, unless you’re not on your boat and didn’t leave an anchor watch.

You Set the Rule

You come around the point to the “hot spot” on a summer Saturday and you’re the first to arrive. When that happens, the basic rule is to set two anchors – bow and stern – which allows more boats to enjoy the day. After you’ve set the two hooks, you can call “first in”, and there’ll be the usual shouting when the fleet arrives, but you’ll be there, and in good shape.

Don’t Be In A Hurry to Get Off

As tempting as it may be, don’t jump into the dinghy with your picnic or clamming basket in hand. Take the time to be sure you’re not dragging the hook. Take a couple of “ranges”, by lining up two stationary object ashore – in two or more directions – a couple of trees, rocks, etc. Wait a while, and if they stay in line, you are secure. Then go where you must go. Leaving crew on “anchor watch” to deal with emergencies is a good plan if you’re going to out of sight of the boat.

Now you’re a good anchor neighbor. Etiquette means good manners, and good manners make friends.

Boat Tow or No?

The obligation to render assistance is as old as the sea. You see another vessel in danger, and you go to help. Generally, there’s no excuse to not at least try, even if it’s a boat tow.

Reasons To Say NO

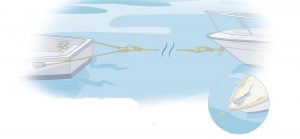

Even though boats seem to float and drift easily, they’re still heavy. That means some interesting loads on the towing boat. A few thousand pounds of boat at the the end of a lightweight tow line can get “western” in a hurry, even in flat water and no wind. Add some seas or a heavy chop and some real breeze and the tow can go bad quickly.

Most boats have relatively lightweight cleats, and most boaters don’t carry heavy lines – snapping lines and ripped out cleats aren’t helping your boat, or the boat you’re trying to help. It’s also likely that your power and props are just fine for motoring, fishing or skiing, and just aren’t suited for generating the torque necessary for towing a heavy load at lower speeds. Think about pulling another car on a wet road, spinning your tires the whole way. Probably not a good idea.

What About the Line?

A tow line should be eight or ten boat lengths (call it 250 to 300 feet) if you’re pulling a 30 foot boat. Most pleasure boats don’t carry line long enough or strong enough for serious towing. If you do have line, the worst to use is the standard three-strand nylon, since it has too much stretch, and tends to part explosively under load. Double-braided nylon is a better choice, but like any line that sinks, you’ll run the risk of fouling your props, if you allow too much slack. Your best bet is probably your anchor line, as it’s usually the longest and strongest line aboard.

Points and Cleats

Before you use that cleat or pad eye, first make sure it’s up to the task at hand. A too small cleat (even sometime a Forespar), a cheap cleat or poor installation can and will break, and can become a lethal missile if it snaps under load. Then, when you’re setting up the tow rig, use a “bridle” set forward with the length of each leg at least twice the width of your boat, distributing the tow load to both side of the boat, allowing you to maintain control, since a single line attached to the transom will truly degrade your steering. Then, adjust the tow line length so that your boat and the tow are in sync with the waves and troughs (remember that if you’re towing, the other boat probably doesn’t have brakes, so the tow tine may need to be slightly longer than you think).

A Knotty Issue

Knots used in towing are subject to heavy loads, so avoid knots that cinch tight. Cleat hitches and bowlines are ideal, as they won’t come untied under load, but are easy to release when required. And, no one stands in direct line with a loaded line (or should be dumb enough to straddle it), because if the line or cleat lets go, someone gets hurt.

Wait It Out

If there’s only one thing to take way here, it is to err on the side of caution. If you aren’t very sure of your ability to tow the other boat safely and effectively, don’t do it. The last thing the Coast Guard wants is two boats in trouble at the same place and time. Get on the radio and stand by for help, preferable a vessel with the equipment, know-how and insurance.

And thanks to the U.S. Coast Guard for their guidance, and not least, being ready to help us when and where it’s needed.

Trafalgar Revisited

Transcript of conversation on the quarterdeck of HMS Victory on October 21, 1805 off the coast of Spain near Cape Trafalgar, between Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson and his Flag Captain Sir Thomas Hardy. Twenty-two English ships of the line faced a combined French and Spanish fleet of thirty-three ships of the line. The English won a dramatic and history-changing victory.

We assume a more modern regulatory environment.

Nelson: “Order the signal, Hardy.”

Hardy: “Aye, aye sir.”

Nelson: “Hold on, that’s not what I dictated to Flags. What’s the meaning of this?”

Hardy: “Sorry sir?”

Nelson (reading aloud): “‘ England expects every person to do his or her duty, regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, religious persuasion or disability.’ – What gobbledegook is this?”

Hardy: “Admiralty policy from the Human Capital Management team, I’m afraid, sir. We’re an equal opportunities employer now. We had the devil’s own job getting ‘England ‘ past the censors, lest it be considered racist.”

Nelson: “Gadzooks, Hardy. Hand me my pipe and tobacco.”

Hardy: “Sorry sir. All naval vessels have now been designated smoke-free working environments.”

Nelson: “In that case, break open the rum ration. Let us splice the mainbrace to steel the men before battle.”

Hardy: “The rum ration has been abolished by the HHS Department, Admiral. It’s part of the Government’s policy on binge drinking.”

Nelson: “Good heavens, Hardy. I suppose we’d better get on with it ………. full speed ahead.”

Hardy: “I think you’ll find that according to EPA there’s a 4 knot speed limit in this stretch of water.”

Nelson: “Damn it man! We are on the eve of the greatest sea battle in history. We must advance with all dispatch. Report from lookouts in the crow’s nest please.”

Hardy: “That won’t be possible, sir.”

Nelson: “What?”

Hardy: “Health and Safety have closed the crow’s nest, sir. No harness; and they said that rope ladders don’t meet regulations. They won’t let anyone up there until proper scaffolding can be erected.”

Nelson: “Then get me the ship’s carpenter without delay, Hardy.”

Hardy: “He’s busy knocking up a wheelchair access to the foredeck Admiral.”

Nelson: “Wheelchair access? I’ve never heard anything so absurd.”

Hardy: “Health and Safety again, sir. We have to provide a barrier-free environment for the differently abled.”

Nelson: “Differently abled? I’ve only one arm and one eye and I refuse even to hear mention of the word. I didn’t rise to the rank of admiral by playing the disability card.”

Hardy: “Actually, sir, you did. The Royal Navy is underrepresented in the areas of visual impairment and limb deficiency.”

Nelson: “Whatever next? Oh well – Order full sail. The salt spray beckons.”

Hardy: “A couple of problems there too, sir. Health and Safety won’t let the crew up the rigging without hard hats. And they don’t want anyone breathing in too much salt – haven’t you seen the memos?”

Nelson: “I’ve never heard such infamy. Break out the cannon and tell the men to stand by to engage the enemy.”

Hardy: “The men are a bit worried about shooting at anyone, Admiral.”

Nelson: “What? This is mutiny!”

Hardy: “It’s not that, sir. It’s just that they’re afraid of being charged with murder if they actually kill anyone. There are a couple of legal-aid lawyers on board, watching everyone like hawks.”

Nelson: “Then how are we to sink the Frenchies and the Spanish?”

Hardy: “Actually, sir, we’re not.”

Nelson: “We’re not?”

Hardy: “No, sir. The French and the Spanish are our European partners now. According to the Common Fisheries Policy, we shouldn’t even be in this stretch of water. We could get hit with a claim for compensation. And, sinking ships puts us into environmental trouble again.”

Nelson: “But you must hate a Frenchman as you hate the devil.”

Hardy: “I wouldn’t let the ship’s diversity co-ordinator hear you saying that sir. You’ll be up on a disciplinary report.”

Nelson: “You must consider every man an enemy, who speaks ill of your King.”

Hardy: “Not any more, sir. We must be inclusive in this multicultural age. Now put on your Kevlar vest; it’s the rules. It could save your life”

Nelson: “Don’t tell me – Health and Safety. Whatever happened to rum and the lash?”

Hardy: As I explained, sir, rum is off the menu! And there’s a ban on corporal punishment.”

A few minutes later, Nelson was struck down by a musket ball. His last words were: “Kiss me, Hardy”, which opens another channel of regulatory inquiry.

Thanks to and cribbed and edited from a post on Cruisers Forum….

Forespar® Gives Back

- How important is a friendly smile?

- Does it matter if we extend a helping hand to those who are less fortunate than ourselves?

- Is supporting legitimate charities important?

Scott Foresman, the owner of Forespar® Products – considers “Giving Back” a basic, very important and essential core value philosophy.

From humble beginnings 50 years ago, today Forespar® manufactures 95% of its products in Rancho Santa Margarita, California. Forespar is a trusted supplier of proprietary inventions and accessory products designed for sail and power boats, non-toxic and natural performance care products for recreational vehicles, automotive and home use.

Forespar’s “Giving Back” candidates are diverse. Through careful evaluation, Forespar® exclusively supports and contributes to organizations that lend a helping hand – whether a medical problem, honoring wounded warriors, children who suffer from debilitating diseases or those in the community who benefit from support, hope and healing programs.

Aligning with the firm’s strong core family values, Forespar ® chose charity and non-profit organizations that observe balance of social relevancy and adhere to charters focusing on highly efficient funding that support the “cause” rather than “administration”.

Forespar® is Honored to Work With the Following Champions in its “Giving Back” Program:

- Shriners Hospitals – Treats cancer and children injuries; Parents never have to pay to their children’s care.

- Navy Seal Foundation – Immediate and ongoing support tailored to Navy SEALs and their families.

- Special Operations Warrior Foundation – Helps families of those who died or were severely wounded in service to the country.

- Coast Guard Foundation – Education, support, and relief for USCG members and their families.

Foresman comments that the company plans to continue and expand its philanthropic activities.

10 Commandments of Beercan Racing

Sailors and clubs across the world hold casual races on weekday evenings. In the US, we often refer to them as “Beercan Races”, supposedly because back in the day you could track the race course by the trail of beer cans floating in the bay. We’re a lot greener today, but the concept holds true: Race to win, but if you’re not having fun, go home. There are basic commandments that govern the sub-sport:

Sailors and clubs across the world hold casual races on weekday evenings. In the US, we often refer to them as “Beercan Races”, supposedly because back in the day you could track the race course by the trail of beer cans floating in the bay. We’re a lot greener today, but the concept holds true: Race to win, but if you’re not having fun, go home. There are basic commandments that govern the sub-sport:

I. Thou shalt not take anything other than safety too seriously. Relax, have fun and keep it light. Late to the start? So what. Over early? No big thing. Too windy? Quit. No breeze? Break out the beer. The point is to have fun, but stay safe. To overquote, “Safe boating is no accident”.

II. Thou shalt honor the rules if thou knowest them. US Sailing amends and publishes the Racing Rules of Sailing on a regular basis, and unless your Sailing Instructions say otherwise, this is the racing Bible. Few sailors other than PRO’s, Judges and rabid racers have studied it cover to cover, since it’s about as interesting and exciting as the Tax Code. For beer can racing, you can get by if you remember the biggies (port tack boats avoid starboard tackers, windward boards avoid leeward ones, and outside boats give room at the marks). Another major is the Law of Tonnage: Stay out of the way of the bigger boats, because even if you’re right, getting run over by a big kid still hurts. So, pay your insurance premiums, and keep a low profile unless you’re sure you know what you’re doing. In other words – Common Sense.

III. Thou shalt not run out of beer. Self explanatory. There’s a reason these are not called milk bottle, coke can, or hot chocolate races. However, our club does have a tequila sponsor for our Taco Tuesday series.

IV. Thou shalt not covet thy competitor’s boat, sails, equipment, crew or PHRF rating. No whining; If you’re lucky enough to have a sailboat, go out and use it! You don’t need that latest in zircon bearing diamond encrusted widgetry or unobtanium sailcloth to have a great time on the water with your friends (unless it’s a Forespar pole). Even if your boat is a heaving pig, set modest goals and work toward them. Or don’t – it’s only beer can racing.

V. Thou shalt not amp out. Save that stuff for the freeway or, if you must, Saturday’s “real” race. Remember what happened to Captain Bligh, and realize that if you lose it on Wednesday night, you’re going to run out of crew – and friends – in a hurry. Chill out. Nobody’s going to read about this race in Sailing World.

VI. Thou shalt not protest thy neighbor. This is extremely tacky (pun intended) at this level of competition. It’s justifiable if there’s damage, and blame needs to be established, but on the whole, tossing a red flag is the height of bad taste in something as relatively inconsequential as a beer can race. Besides proving that you’re clueless about the concept, it screws up everybody’s evening. Don’t do it – its bad karma.

VII. Thou shalt not screw up thy boat. We all know a hardcore warrior who blew out his main on Thursday and had to sit out a big race on Saturday. It’s just not worth risking your boat and gear in such casual competition. Avoid other boats at all costs, and stay away from hard objects – buoys, docks, pilings and paddleboards. If you have two sets of sails, use the old ones.

VIII. Thou shalt always go to the yacht club afterward. Part of the gestalt of beer can races is bellying up to the yacht club bar post race. Corinthian etiquette demands that you congratulates the winners, and buy a round for your crew. And, the bar is the logical place to meet old friends and make new ones.

IX. Thou shalt bring thy spouse, kids, friends and whoever else wants to go. Beer cans are great for introducing folks to sailing – neighbors, house guests, co-workers, the dog, and there’s usually someone hanging on the dock that would like to go. When has there ever been an overabundance of crew? Of course, there’s one our regulars who sails with as many 18 souls on a 45-foot boat for the inside the harbor races. And, remember the “No Passengers” adage. Give everyone a job on the boat. it’s more fun that way.

X. Thou shalt not worry; thou shalt be happy. Leave the phones in the car, bring some tunes. Relax, it’s not the America’s Cup.

See you out there.

Mike Dwight

Thanks to Latitude 38 for the original and illuminated texts

Single Engine Parking

It’s a narrow channel, and and a tight dock space. Worse yet, you’ve got a single engine, along with its single prop. Conventional wisdom tells you that you’re going have a tough time docking the boat  because of that single screw, without a lot of practice. Conventional wisdom is wrong.

because of that single screw, without a lot of practice. Conventional wisdom is wrong.

Yes, it’s easier with twins. You can back one, forward the other, spin the boat to line it up, both forward (or astern) and ease your way alongside the dock without touching the wheel. With a single many of us angle the bow toward the dock and add power while swinging the helm at the last second and hoping that we don’t bash the dock or stick the bow into boat ahead, which usually involves a quick pop of reverse power. Or come up a little too far away having to go around and try again

Don’t say you’ve never done any of the above. However, there are some simple rules that when applied will work:

Most important – the stern moves First! We think and feel the bow turning just like the car does, when in fact the boat turns by pushing the stern to one side or the other with pressure on the rudder, and forward motion pushes the bow around. If you keep this in mind (to the point that you don’t have to think about it), life with a single is easier.

Second – forget the throttle. Just put the boat into gear, preferably at idle. She will move, and you shouldn’t be in that much of a hurry.

Third – easy into the dock space. Pull up parallel to the dock space and a few feet away. Yes, parallel. Then, crank the helm all the way away from the dock, and slip the gear into forward for about two seconds. The immediately go to reverse for the same time interval. Repeat as necessary, and you’ll find your boat moving sideways into the dock.

Last, wind and current can help or hinder. And, you’ll want to compensate accordingly. Obviously, an onshore breeze is really nifty when it helps push you to the dock, An offshore breeze is going make you work harder to get there. Often, taking down canvas and covers reduces the windage, making things more manageable. Opening the windows reduces wind surface, sometimes to surprising extent. Current can be as, if not more, interesting, but usually solvable if you just make your starting point a bit up the current, and let it push you down into your space while you’re working the boat.

You don’t have be brave or too proud. If you’re having tough time, look over on the dock. When there are people there, many if not most will be happy to help if you just ask. And, most of the time, you can just pull away, go around and start over. You’ll get it in there.

And as in most things nautical, practice helps.

Mike Dwight