Forespar's Point of View

Blogging About Life on the WaterAbout Mike Dwight

View all posts by Mike Dwight

Keep Your Nose Up

One of the first times I ran outside the harbor on my own, the waves were small and relatively smooth. But when I returned a couple of hours later, the tide had changed against the wind, the chop had turned into waves, and the breeze had gone from eight to about fifteen knots. And, of course I was coming downwind with following sea. In a 14-foot centerboard boat. With all the vast experience and skill of a 12-year old.

Eased the centerboard up, surfed down the face of the wave, stuffed the bow and broached the boat. After what seemed like a dozen times almost righting the boat, a real sailor came up (in a power boat) and instructed me on getting the main in the boat, the boat upright and into the harbor, wet cold and alive. I’ve tried to repeat the experience in larger boats, but was unable to replicate the conditions, probably because there’s usually crew aboard who don’t want to get that wet, and I have many more years of experience driving boats. I’ve even tried to do the same thing with a power boat, almost succeeding due largely to inattention.

Three basic lessons learned for following seas:

- Trim the bow up. That’s why sailboats seem to keep the weight in the stern when running down the sea. If you’re in a power boat, pay attention to the trim tabs.

- Learn to surf the boat. Do not drive directly down the wave, because the bow will slow the boat when it hits the back of the wave ahead, and the following sea is likely to push your stern to the side, inducing that “I wanna broach ” motion.

- Unless you’re racing, try to find a spot on the back of the wave – a lot easier to do with a power boat – so you don’t get pushed around as much or as suddenly. In other words, slow down to the speed of the wave if you can. It’s safer and a whole lot more comfortable.

The oft used cliche “Slower is smoother, and smoother is fast” sounds odd, but it applies. You’ll reach your destination both drier, and happier.

First and Only Train Ride to Catalina

A bit of yachting history

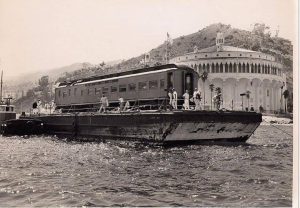

In 1963, a group of Southern California yachtsmen decided that a train ride to Avalon was in order. They did exactly (sort of) that as you can see from the photo of the Pullman car at the Casino in Avalon.

The car was acquired by a regional railroad magnate; McFadden, of the family who were the original operators of Newport Beach. The car was loaded onto a barge in Long Beach and towed/pushed by tugs to the island.

The only comment by the co-skippers was that the 26-mile railroad bed was somewhat soggy and ride was a bit uneven.

Contributions Made To Community Sailing In Bill Mosher’s Name

Milwaukee Community Sailing Center Receives Over $7000 To Foster Youth Sailing & Renames Annual Lobster Boil Fundraiser In His Honor

Forespar Products and the Milwaukee Community Sailing Center combined to raise a total of $7215 in funds to honor long time industry professional and Forespar representative William (Bill) Mosher. These contributions reflect individual donations from Forespar employees and Milwaukee Community Sailing Center members, as well as a matching donation from Forespar based on the received amount. Additionally, the Milwaukee Community Sailing Center announced that it will rename their annual lobster boil fundraiser in Bill’s honor.

Forespar Products and the Milwaukee Community Sailing Center combined to raise a total of $7215 in funds to honor long time industry professional and Forespar representative William (Bill) Mosher. These contributions reflect individual donations from Forespar employees and Milwaukee Community Sailing Center members, as well as a matching donation from Forespar based on the received amount. Additionally, the Milwaukee Community Sailing Center announced that it will rename their annual lobster boil fundraiser in Bill’s honor.

Hired as the original Executive Director of the Milwaukee Community Sailing Center in 1979, Bill was a strong force in establishing and driving the organization forward throughout the years. When he unexpectedly passed away in July 2015, Forespar offered to donate matching funds for donations made to the MCSC in Bill’s name. One year later the campaign’s funds have been realized and over $7000 of total donations will be used to help fund a successful STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Math) youth sailing program and a portion of a needed “new” safety boat.

The Milwaukee Community Sailing Center has also decided to rename its popular annual lobster boil fundraiser in Bill’s honor. Now known as the Bill Mosher Memorial Lobsta Boil, the event will be held on the MCSC grounds, August 27th. A memorial “rock” and plaque will also be dedicated to Bill’s lifelong efforts during the event.

Forespar® is one of the oldest, most established boat hardware manufacturers in the United States. They are the number one manufacturer of downwind sailing poles and their diverse line of marine products includes Leisure Furl™ boom furling systems, Marelon® plumbing fittings and numerous other marine related products.

The Milwaukee Community Sailing Center is a private, not-for-profit 501 (c) 3 agency located just north of downtown in the heart of Veterans Park at McKinley Marina. MCSC provides educational and recreational sailing programs to those who wish to gain access to Lake Michigan and learn to sail; regardless of age, physical ability or financial concerns.

For more information visit www.sailingcenter.org or email kenq@broadreachmarketing.net

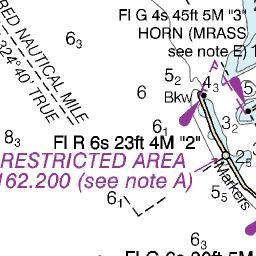

Olympics: A sailing surprise as the water and conditions are ideal on Guanabara Bay

RIO DE JANEIRO – Sailing, not the dirty water, was finally the focus on troubled Guanabara Bay during a spectacular start to the Olympic regatta.

Windsurfers sped across the waves toward Flamengo Beach in a fresh breeze, against the imposing backdrop of Sugarloaf Mountain. Christ the Redeemer, Rio’s highest and most magnificent landmark, was obscured by fog.

Across the bay, 43-year-old Robert Scheidt won the second race in the Laser class after finishing a disappointing 23rd in the opener. He’s trying to become the first Olympic sailor and first Brazilian to win six Olympic medals. He owns two golds, two silvers and a bronze. He’s seventh overall.

Charlie Buckingham of Newport Beach, making his Olympic debut in the Laser class, said the water “was great. No trash. It was warm. Splashes felt good.”

Buckingham finished 20th and seventh in the two races Monday, with eight races to go before the medal race.

Guanabara Bay seemed to pass the sniff test, at least on the surface.

The courses appeared clear of trash. Organizers have sent a helicopter over the bay every morning searching for rubbish. If any is spotted, boats are sent to scoop it up. Barriers have been put across rivers to try to stem the flow of garbage into the bay.

Under the waves, things are different.

An independent study by The Associated Press has shown high levels of viruses and sometimes bacteria from human sewage in the water.

“We’re not really concerned about that,” Pascual said. “We’ve been here for a while training and we’ve hadn’t had an issue. I’m just focused on racing. There’s been days when it rains you can see stuff floating around, but it’s like everywhere else I guess. It’s a bay.”

American Paige Railey, who finished second in the second Laser Radial race and is seventh overall, said the water was “great, totally fine. Warm, clean. We were happy. I really want to give hats off to Brazil. I came here in 2007 for the Pan Ams and they’ve done a magnificent job of cleaning up the water and there are really no problems. I’d jump off the boat and go swimming if I could.”

“This is like perfect conditions. You can’t get better than this. And the views are amazing,” said American windsurfer Pedro Pascual of Miami.

Conditions could change if it rains.

“There always have been problems here, Spanish windsurfer Ivan Pastor said. “It’s a very large bay. There is a lot of current, rivers flowing into it and we’ve seen quite frequently a lot of trash floating; plastic, which is the worst.”

Pastor said he’s not afraid of swallowing the water.

“I’ve been here a lot and fallen and it hasn’t been with my mouth closed,” he said. “Knock wood. Nothing has happened. It looks very clean today. There have been other years here when it was really dirty.”

Croatia’s Tonci Stipanovic led the Laser class while China’s Lijia Xu led the Laser Radial. Nick Dempsey of Great Britain and Charline Picon lead the windsurfer classes.

Mack Sails & Forespar – A Solid Combo

Something Big This Way Commeth …

when in 1967 Swedish Sailmakers, a Fort Lauderdale fledgling sailmaking firm, partnered with lifelong sailor Brad Mack and Bradford Mack & Co was launched. For the next 20 years, the company continued to expand and in 1988 moved to Stuart, FL and was renamed Mack Sails. Over the years the company has expanded to include a full service rigging shop and a complete marine electronics service . Every Mack Sail is made in Stuart, FL and “…we insist that each one is made from the very best cloth and hardware.”

Brad Mack’s two sons, Travis Blain and Colin Mack , grew up in sail boats racing, cruising, or in the sail loft “learning the ropes.” After college Travis and Colin officially joined the firm and in 2002, took the helm, sharing the management and striving to deliver an extraordinarily designed and crafted product.

Colin and Travis remember the old days when they were ‘sponges’ learning everything possible at a rapid fire pace. “The lessons have all paid off because without the encouragement and guidance of our dad, the company could never have become what it has today.”

For close to 50 years the family tradition of pride and commitment to quality service sets Mack Sails apart based on these standards:

- Pride in every sail we manufacture – all designed for speed and durability

- Only the highest quality U.S. woven and finished cloth and tapes are used in our sails

- Hands on customer service begins with the initial contact and continues all the way through sail and rigging delivery and installation

Strong relationships have played a significant role in Mack Sails’ growth. In 1967, a key affiliation with Forespar began when Brad reached out across the U.S. for like-minded entrepreneurs who held similar strong business and family values. For the next 40 plus years, the Mack Sails and Forespar® relationship thrived and remains an industry symbol of ‘partnering for progress’ for both entities.

What the collaboration with Forespar stands for is simple, according to Travis. Mack Sails has worked with them on many projects (one of the first hydraulic Leisure Furl™ booms – aluminum or carbon fiber booms offer safety and convenience of In-Boom mainsail reefing and furling systems from the safety of the cockpit .)

“Collectively, we pooled resources and were the first ever to design and install a large roached full batten main for a Leisure Furl™ boom furling system on a Lagoon 440,” said Travis.

Colin says, “Throughout this journey, we’ve blended excellent products and service that satisfies the most demanding and rigorous standards that sailors demand. Forespar makes the boom furlers, and we make the sails and install them (riggers and sailmakers). This collaboration extends beyond the U.S., with LeisureFurl installations most recently as far away as Italy and Trinidad.”

“Forespar has developed a very good LeisureFurl™ design that allows Mack Sails no restrictions on multi-hulls; because of that we sell more of their booms and we install the boom systems and sails in sync, ” Colin concluded.

Forespar Vice President Bill Hanna sees the strong bond between both companies as a significant advantage to Forespar’s success over the years. “Though they are located in Florida, the Mack Sails team is always a phone call away…it’s as if they were in the office right next door. Our collaborations have become almost seamless because we’ve shared building and delivering quality boom systems, sails and rigging for nearly 50 years!”

Mike Dwight

Further: Kids on the Water

After the 100-foot Comanche crushed the Newport Bermuda Race record by almost five hours, finishing June 19, it has taken the next boat over two more days to reach Bermuda. While Comanche’s finish position was predicted, few could say the same about the runner-up.

High Noon, at 41 feet, is fully 59 feet shorter than Comanche and tens of feet shorter than many other of the 142 starters. Yet High Noon was the second boat to finish , and did so with a 10-person crew, seven of which are teenagers between ages 15 and 18.

This is all about old/new ideas in training young sailors. For decades they sailed only small boats. Enter Peter Becker, who sails out of American Yacht Cub, in Rye, New York. He was an eager 15-year-old when he sailed his first Newport Bermuda Race. “I was the kid on the boat, up on the bow changing sails,” he recalls. Since then he’s done 16 more Bermuda Races and a race from New York to Barcelona, Spain.

Four years ago his teenage children were getting interested in ocean racing, and he came up with a new approach: a unique training program at his club that came to be called the Young American Junior Big Boat Sailing Team.

He put youngsters in a J/105 racing in local regattas under the his tutelage and that of other big-boat sailors.

From there the youth sailors crewed on short, then longer ocean races, even delivering boats home after the races. It worked so well that for the 2016 Newport Bermuda Race, the US Merchant Marine Academy Sailing Foundation loaned High Noon to his program.

The results are apparent. You need crew? Draft juniors. They’re often as good or better than you are – and a whole lot more agile.

Get the Kids on the Water!

It’s about time.

US Sailing and others are pushing to get kids and young people out on the water sailing. Not necessarily racing, but sailing.

My suggestions may be facile, but: (a) Start them early, and (b) Keep them involved in the process when they’re out there – no passengers.

Our primary YC offers one of the finer Juniors’ programs on the West Coast. While we have some superb racers in the Junior ranks, many race in the Harbor for the competitive fun of it, many sail just for the fun. We start Juniors in the “Starfish” program at about age five, when we can. They’re more at summer camp than on the water, but they are exposed to fun part of boating, with a dose of responsibility. that can then graduate to on the water, first sailing with coaches, then Sabots (racing if they want to), then Optis, then Lidos for fun, or 420’s to race, etc.

And, while we’re at it, there are a number of racing skippers who make sure that competent (meaning safe) juniors, mostly adolescents, crew on their boats for local PHRF races, and even on some of the distances races – again, no passengers. One skipper sailed the Newport-Ensenada race with eight kids and four adults, finishing fifth in a class of 15. All the juniors on that crew are sailing. Five are still racing , three on a national level, and three sail for fun.

The end result has been sailors who started in the Club at five, with about half of a twenty-year program philosophy still sailing (and that doesn’t count the power boaters). That means BCYC Junior sailing program has produced about 200 sailors still on the water, and more than that overall in recreational boaters.

That also means a pretty good crew pool for those of us who race a lot.

Make it fun, and they will come.

Overboard at Night

Overboard at Night – Newport to Ensenada Race

A Farr 40 was doing about 15 knots downwind in a 20-knot breeze. It was Friday night about 8pm, after the noon start, and they were just off the Coronado Islands. Good breeze, good speed. and about halfway down the course. Great N2E race so far.

Large wave slaps the stern, causing an ugly round down. One of the crew slip under the lifeline and into the sea. No harness, no leash, and no PFD or light on him or four of the other five crew. On top of that, he broke his arm badly on the way over the side.

Large wave slaps the stern, causing an ugly round down. One of the crew slip under the lifeline and into the sea. No harness, no leash, and no PFD or light on him or four of the other five crew. On top of that, he broke his arm badly on the way over the side.

The only crew wearing a PFD grabs the tiller, and she gets the boat back up. About 500 yards later, they’ve got the boat back under control and the kite back in the boat. They get the engine started, and head back upwind in 20+ knots and fairly big waves looking for their lost guy.

They found him.

Why? They did some things right. While one sailor launched the Man Overboard gear, another kept pointing at the spot where he hit the water. The MOB pole was lighted, and a float was part of that gear. And they launched it in a timely manner, enabling the swimmer to get to it under difficult (to say the least) conditions. After wrestling with an injured sailor (a 200-pound man, with one usable arm, wearing wet foulies) and the Life Sling, they got him aboard. And, yes, the Coast Guard helo did show, but it was easier to abandon the race and get him to San Diego than deal with an air rescue off a sailboat in the wind and sea conditions.

When was the last time we heard about someone going over the side under those circumstances, and being found, much less alive? Kudos to the Foil crew for reacting well in a bad situation.

I’m serious about that kind of safety – jack lines, harnesses, etc. The crew on my boat get a little peeved when I insist on all that stuff after dark, especially when it’s bumpy out there. Wear it, and rig it. And make sure you’ve got good MOB gear and know how use it. You may never need it, and let’s hope that’s the case, but when you do, it saves a life!

Mike Dwight

Drone Ships on the Way?

Unmanned freighters appear to be on the horizon, and headed our way. We’ve got unmanned spacecraft and drone aircraft and driverless cars, so why not unmanned ships?

Plans for operating unmanned ships were unveiled last month, when Rolls Royce presented a prototype control center, from which crews of seven to 14 people can control fleets across the globe. The mechanics of remote control are already in hand – many of us have some form of auto-pilot on our boats, so it’s not that much of a leap, despite the instant questions: What if something breaks? What about that satellite glitch – as in recent GPS issues?

Those of us who sail, fish, cruise or all of the above in waters off major ports such as LA, New York, Miami, Tampa, Seattle, etc., take some comfort in knowing that those windows on the bridge have a human or two who are actually looking though them for large and small obstacles.

I’ve even seen a ship coming into Long Beach slow to allow a race fleet to pass in front, because some skippers thought they could make it under his bow – I can tell you that if he hadn’t, there would have a been a couple fewer sailboats on the ocean, and the gene pool would have been a bit smarter. That’s the exception to the rule. As we should know, ships don’t have brakes, and that’s a lot of mass moving, usually faster that we are.

So, let’s pay attention to developments on the concept. Colregs and sanity aside, whether there’s a human at the helm or a drone operator in Finland driving that ship, the “law of tonnage” applies (something that we at Forespar understand). Risking your boat and crew on someone else’s satellite link might not be the best plan for longevity.

Mike Dwight