Forespar's Point of View

Blogging About Life on the WaterAbout Mike Dwight

View all posts by Mike Dwight

Boat Tow or No?

The obligation to render assistance is as old as the sea. You see another vessel in danger, and you go to help. Generally, there’s no excuse to not at least try, even if it’s a boat tow.

Reasons To Say NO

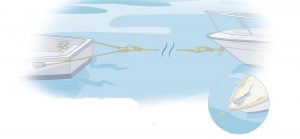

Even though boats seem to float and drift easily, they’re still heavy. That means some interesting loads on the towing boat. A few thousand pounds of boat at the the end of a lightweight tow line can get “western” in a hurry, even in flat water and no wind. Add some seas or a heavy chop and some real breeze and the tow can go bad quickly.

Most boats have relatively lightweight cleats, and most boaters don’t carry heavy lines – snapping lines and ripped out cleats aren’t helping your boat, or the boat you’re trying to help. It’s also likely that your power and props are just fine for motoring, fishing or skiing, and just aren’t suited for generating the torque necessary for towing a heavy load at lower speeds. Think about pulling another car on a wet road, spinning your tires the whole way. Probably not a good idea.

What About the Line?

A tow line should be eight or ten boat lengths (call it 250 to 300 feet) if you’re pulling a 30 foot boat. Most pleasure boats don’t carry line long enough or strong enough for serious towing. If you do have line, the worst to use is the standard three-strand nylon, since it has too much stretch, and tends to part explosively under load. Double-braided nylon is a better choice, but like any line that sinks, you’ll run the risk of fouling your props, if you allow too much slack. Your best bet is probably your anchor line, as it’s usually the longest and strongest line aboard.

Points and Cleats

Before you use that cleat or pad eye, first make sure it’s up to the task at hand. A too small cleat (even sometime a Forespar), a cheap cleat or poor installation can and will break, and can become a lethal missile if it snaps under load. Then, when you’re setting up the tow rig, use a “bridle” set forward with the length of each leg at least twice the width of your boat, distributing the tow load to both side of the boat, allowing you to maintain control, since a single line attached to the transom will truly degrade your steering. Then, adjust the tow line length so that your boat and the tow are in sync with the waves and troughs (remember that if you’re towing, the other boat probably doesn’t have brakes, so the tow tine may need to be slightly longer than you think).

A Knotty Issue

Knots used in towing are subject to heavy loads, so avoid knots that cinch tight. Cleat hitches and bowlines are ideal, as they won’t come untied under load, but are easy to release when required. And, no one stands in direct line with a loaded line (or should be dumb enough to straddle it), because if the line or cleat lets go, someone gets hurt.

Wait It Out

If there’s only one thing to take way here, it is to err on the side of caution. If you aren’t very sure of your ability to tow the other boat safely and effectively, don’t do it. The last thing the Coast Guard wants is two boats in trouble at the same place and time. Get on the radio and stand by for help, preferable a vessel with the equipment, know-how and insurance.

And thanks to the U.S. Coast Guard for their guidance, and not least, being ready to help us when and where it’s needed.

Single-Handed Spinnaker Sailing

We all like spinnaker sailing, but seldom try it single-handed. Take this lesson, but remember that he’s using auto helm for his tiller. If you’re sailing in a smaller to medium boat in light or low-moderate air (under 12 knots), this will work. Any stronger breeze, especially at sea, and single handed kite flying will get “varsity” in a hurry.

Trafalgar Revisited

Transcript of conversation on the quarterdeck of HMS Victory on October 21, 1805 off the coast of Spain near Cape Trafalgar, between Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson and his Flag Captain Sir Thomas Hardy. Twenty-two English ships of the line faced a combined French and Spanish fleet of thirty-three ships of the line. The English won a dramatic and history-changing victory.

We assume a more modern regulatory environment.

Nelson: “Order the signal, Hardy.”

Hardy: “Aye, aye sir.”

Nelson: “Hold on, that’s not what I dictated to Flags. What’s the meaning of this?”

Hardy: “Sorry sir?”

Nelson (reading aloud): “‘ England expects every person to do his or her duty, regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, religious persuasion or disability.’ – What gobbledegook is this?”

Hardy: “Admiralty policy from the Human Capital Management team, I’m afraid, sir. We’re an equal opportunities employer now. We had the devil’s own job getting ‘England ‘ past the censors, lest it be considered racist.”

Nelson: “Gadzooks, Hardy. Hand me my pipe and tobacco.”

Hardy: “Sorry sir. All naval vessels have now been designated smoke-free working environments.”

Nelson: “In that case, break open the rum ration. Let us splice the mainbrace to steel the men before battle.”

Hardy: “The rum ration has been abolished by the HHS Department, Admiral. It’s part of the Government’s policy on binge drinking.”

Nelson: “Good heavens, Hardy. I suppose we’d better get on with it ………. full speed ahead.”

Hardy: “I think you’ll find that according to EPA there’s a 4 knot speed limit in this stretch of water.”

Nelson: “Damn it man! We are on the eve of the greatest sea battle in history. We must advance with all dispatch. Report from lookouts in the crow’s nest please.”

Hardy: “That won’t be possible, sir.”

Nelson: “What?”

Hardy: “Health and Safety have closed the crow’s nest, sir. No harness; and they said that rope ladders don’t meet regulations. They won’t let anyone up there until proper scaffolding can be erected.”

Nelson: “Then get me the ship’s carpenter without delay, Hardy.”

Hardy: “He’s busy knocking up a wheelchair access to the foredeck Admiral.”

Nelson: “Wheelchair access? I’ve never heard anything so absurd.”

Hardy: “Health and Safety again, sir. We have to provide a barrier-free environment for the differently abled.”

Nelson: “Differently abled? I’ve only one arm and one eye and I refuse even to hear mention of the word. I didn’t rise to the rank of admiral by playing the disability card.”

Hardy: “Actually, sir, you did. The Royal Navy is underrepresented in the areas of visual impairment and limb deficiency.”

Nelson: “Whatever next? Oh well – Order full sail. The salt spray beckons.”

Hardy: “A couple of problems there too, sir. Health and Safety won’t let the crew up the rigging without hard hats. And they don’t want anyone breathing in too much salt – haven’t you seen the memos?”

Nelson: “I’ve never heard such infamy. Break out the cannon and tell the men to stand by to engage the enemy.”

Hardy: “The men are a bit worried about shooting at anyone, Admiral.”

Nelson: “What? This is mutiny!”

Hardy: “It’s not that, sir. It’s just that they’re afraid of being charged with murder if they actually kill anyone. There are a couple of legal-aid lawyers on board, watching everyone like hawks.”

Nelson: “Then how are we to sink the Frenchies and the Spanish?”

Hardy: “Actually, sir, we’re not.”

Nelson: “We’re not?”

Hardy: “No, sir. The French and the Spanish are our European partners now. According to the Common Fisheries Policy, we shouldn’t even be in this stretch of water. We could get hit with a claim for compensation. And, sinking ships puts us into environmental trouble again.”

Nelson: “But you must hate a Frenchman as you hate the devil.”

Hardy: “I wouldn’t let the ship’s diversity co-ordinator hear you saying that sir. You’ll be up on a disciplinary report.”

Nelson: “You must consider every man an enemy, who speaks ill of your King.”

Hardy: “Not any more, sir. We must be inclusive in this multicultural age. Now put on your Kevlar vest; it’s the rules. It could save your life”

Nelson: “Don’t tell me – Health and Safety. Whatever happened to rum and the lash?”

Hardy: As I explained, sir, rum is off the menu! And there’s a ban on corporal punishment.”

A few minutes later, Nelson was struck down by a musket ball. His last words were: “Kiss me, Hardy”, which opens another channel of regulatory inquiry.

Thanks to and cribbed and edited from a post on Cruisers Forum….

Forespar® Gives Back

- How important is a friendly smile?

- Does it matter if we extend a helping hand to those who are less fortunate than ourselves?

- Is supporting legitimate charities important?

Scott Foresman, the owner of Forespar® Products – considers “Giving Back” a basic, very important and essential core value philosophy.

From humble beginnings 50 years ago, today Forespar® manufactures 95% of its products in Rancho Santa Margarita, California. Forespar is a trusted supplier of proprietary inventions and accessory products designed for sail and power boats, non-toxic and natural performance care products for recreational vehicles, automotive and home use.

Forespar’s “Giving Back” candidates are diverse. Through careful evaluation, Forespar® exclusively supports and contributes to organizations that lend a helping hand – whether a medical problem, honoring wounded warriors, children who suffer from debilitating diseases or those in the community who benefit from support, hope and healing programs.

Aligning with the firm’s strong core family values, Forespar ® chose charity and non-profit organizations that observe balance of social relevancy and adhere to charters focusing on highly efficient funding that support the “cause” rather than “administration”.

Forespar® is Honored to Work With the Following Champions in its “Giving Back” Program:

- Shriners Hospitals – Treats cancer and children injuries; Parents never have to pay to their children’s care.

- Navy Seal Foundation – Immediate and ongoing support tailored to Navy SEALs and their families.

- Special Operations Warrior Foundation – Helps families of those who died or were severely wounded in service to the country.

- Coast Guard Foundation – Education, support, and relief for USCG members and their families.

Foresman comments that the company plans to continue and expand its philanthropic activities.

Taking Your Friends Out for A Beer Can Race

Suggested taking along friends neighbors, and dock denizens. You’re going to need a bigger boat (like this new Baltic 130), and a fat wallet for the bar tab at the club.

10 Commandments of Beercan Racing

Sailors and clubs across the world hold casual races on weekday evenings. In the US, we often refer to them as “Beercan Races”, supposedly because back in the day you could track the race course by the trail of beer cans floating in the bay. We’re a lot greener today, but the concept holds true: Race to win, but if you’re not having fun, go home. There are basic commandments that govern the sub-sport:

Sailors and clubs across the world hold casual races on weekday evenings. In the US, we often refer to them as “Beercan Races”, supposedly because back in the day you could track the race course by the trail of beer cans floating in the bay. We’re a lot greener today, but the concept holds true: Race to win, but if you’re not having fun, go home. There are basic commandments that govern the sub-sport:

I. Thou shalt not take anything other than safety too seriously. Relax, have fun and keep it light. Late to the start? So what. Over early? No big thing. Too windy? Quit. No breeze? Break out the beer. The point is to have fun, but stay safe. To overquote, “Safe boating is no accident”.

II. Thou shalt honor the rules if thou knowest them. US Sailing amends and publishes the Racing Rules of Sailing on a regular basis, and unless your Sailing Instructions say otherwise, this is the racing Bible. Few sailors other than PRO’s, Judges and rabid racers have studied it cover to cover, since it’s about as interesting and exciting as the Tax Code. For beer can racing, you can get by if you remember the biggies (port tack boats avoid starboard tackers, windward boards avoid leeward ones, and outside boats give room at the marks). Another major is the Law of Tonnage: Stay out of the way of the bigger boats, because even if you’re right, getting run over by a big kid still hurts. So, pay your insurance premiums, and keep a low profile unless you’re sure you know what you’re doing. In other words – Common Sense.

III. Thou shalt not run out of beer. Self explanatory. There’s a reason these are not called milk bottle, coke can, or hot chocolate races. However, our club does have a tequila sponsor for our Taco Tuesday series.

IV. Thou shalt not covet thy competitor’s boat, sails, equipment, crew or PHRF rating. No whining; If you’re lucky enough to have a sailboat, go out and use it! You don’t need that latest in zircon bearing diamond encrusted widgetry or unobtanium sailcloth to have a great time on the water with your friends (unless it’s a Forespar pole). Even if your boat is a heaving pig, set modest goals and work toward them. Or don’t – it’s only beer can racing.

V. Thou shalt not amp out. Save that stuff for the freeway or, if you must, Saturday’s “real” race. Remember what happened to Captain Bligh, and realize that if you lose it on Wednesday night, you’re going to run out of crew – and friends – in a hurry. Chill out. Nobody’s going to read about this race in Sailing World.

VI. Thou shalt not protest thy neighbor. This is extremely tacky (pun intended) at this level of competition. It’s justifiable if there’s damage, and blame needs to be established, but on the whole, tossing a red flag is the height of bad taste in something as relatively inconsequential as a beer can race. Besides proving that you’re clueless about the concept, it screws up everybody’s evening. Don’t do it – its bad karma.

VII. Thou shalt not screw up thy boat. We all know a hardcore warrior who blew out his main on Thursday and had to sit out a big race on Saturday. It’s just not worth risking your boat and gear in such casual competition. Avoid other boats at all costs, and stay away from hard objects – buoys, docks, pilings and paddleboards. If you have two sets of sails, use the old ones.

VIII. Thou shalt always go to the yacht club afterward. Part of the gestalt of beer can races is bellying up to the yacht club bar post race. Corinthian etiquette demands that you congratulates the winners, and buy a round for your crew. And, the bar is the logical place to meet old friends and make new ones.

IX. Thou shalt bring thy spouse, kids, friends and whoever else wants to go. Beer cans are great for introducing folks to sailing – neighbors, house guests, co-workers, the dog, and there’s usually someone hanging on the dock that would like to go. When has there ever been an overabundance of crew? Of course, there’s one our regulars who sails with as many 18 souls on a 45-foot boat for the inside the harbor races. And, remember the “No Passengers” adage. Give everyone a job on the boat. it’s more fun that way.

X. Thou shalt not worry; thou shalt be happy. Leave the phones in the car, bring some tunes. Relax, it’s not the America’s Cup.

See you out there.

Mike Dwight

Thanks to Latitude 38 for the original and illuminated texts

Really Nice Yacht Club

We all tend to think our yacht clubs are the best, with outstanding locations, views and often, history. We are often partially right.

Then, there’s the Royal Yacht Squadron, at Cowes, in England. The building is a castle, built in 1539 by Henry VIII to defend against the French. The club itself was formed in 1815 by a group of “gentleman” yachting enthusiasts, and was given a Royal warrant by George IV (he was a member) in 1815. This was BF (Before Forespar). The crenelations in the wall were built for cannons, and are still used for the race guns (brass cannons).

The white structure on the right of the photo below was added in the 1800’s to accommodate the start/finish line end, and race committees And is now know as “The Verandah”

Two Anchors in Easy Water?

Using two anchors is usually a bad weather practice, or used for security where there are current or wave issues. But how you deploy two sets of ground tackle depends on your situation and a number of variables, including the wind, water depth, sea state, and other boats in the area. For example, do you set both off the bow, or one off the bow and the other off the stern? That tried and true practice does keep the boat from swinging, and keeps your bow in the preferred direction. Most of us use the bow/stern because of current, wind, etc., or in an anchorage where the boat’s swing is likely to be limited by other boats.

The easy way to hook is the simplest. Set the bow anchor, pay out excess rode, and drop the stern hook, then set that by powering forward toward the original hook while taking in the original excess rode. Once the boat is where you want it, cleat off both rodes, making sure you have adequate scope on both anchors.

A second, and confortable way to use two anchors to limit swing is a Bahamian Moor. Set the anchors as above, then walk the stern line around to the bow, and cleat accordingly. Yes, the rodes can get twisted, so check and adjust regularly.

One last item: Remember to buoy/mark the anchors when you can. You never know when a less experienced boater will come in and anchor on top of yours,

Mike Dwight

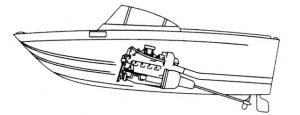

Single Engine Parking

It’s a narrow channel, and and a tight dock space. Worse yet, you’ve got a single engine, along with its single prop. Conventional wisdom tells you that you’re going have a tough time docking the boat  because of that single screw, without a lot of practice. Conventional wisdom is wrong.

because of that single screw, without a lot of practice. Conventional wisdom is wrong.

Yes, it’s easier with twins. You can back one, forward the other, spin the boat to line it up, both forward (or astern) and ease your way alongside the dock without touching the wheel. With a single many of us angle the bow toward the dock and add power while swinging the helm at the last second and hoping that we don’t bash the dock or stick the bow into boat ahead, which usually involves a quick pop of reverse power. Or come up a little too far away having to go around and try again

Don’t say you’ve never done any of the above. However, there are some simple rules that when applied will work:

Most important – the stern moves First! We think and feel the bow turning just like the car does, when in fact the boat turns by pushing the stern to one side or the other with pressure on the rudder, and forward motion pushes the bow around. If you keep this in mind (to the point that you don’t have to think about it), life with a single is easier.

Second – forget the throttle. Just put the boat into gear, preferably at idle. She will move, and you shouldn’t be in that much of a hurry.

Third – easy into the dock space. Pull up parallel to the dock space and a few feet away. Yes, parallel. Then, crank the helm all the way away from the dock, and slip the gear into forward for about two seconds. The immediately go to reverse for the same time interval. Repeat as necessary, and you’ll find your boat moving sideways into the dock.

Last, wind and current can help or hinder. And, you’ll want to compensate accordingly. Obviously, an onshore breeze is really nifty when it helps push you to the dock, An offshore breeze is going make you work harder to get there. Often, taking down canvas and covers reduces the windage, making things more manageable. Opening the windows reduces wind surface, sometimes to surprising extent. Current can be as, if not more, interesting, but usually solvable if you just make your starting point a bit up the current, and let it push you down into your space while you’re working the boat.

You don’t have be brave or too proud. If you’re having tough time, look over on the dock. When there are people there, many if not most will be happy to help if you just ask. And, most of the time, you can just pull away, go around and start over. You’ll get it in there.

And as in most things nautical, practice helps.

Mike Dwight

What’s a Spinnaker Strut?

And Why Do You Need One?

A spinnaker strut is a relatively short (usually aluminum) pole with one end fitting designed for mast attachment, and the other for running a line across a small internal pulley. Standard sizes range up to about seven feet in length and three or four inches in diameter. They look like this:

As its name implies, the strut is for use with a traditional symmetrical spinnaker. It will keep the afterguy (or the spin sheet you’re using as an afterguy) attached to the spinnaker pole away from lifelines, stanchions and other undesirable points on its way back to the stern.

The strut is usually attached to the mast via a padeye on the mast, and often held in position with a sail tie to a shroud

Sailors want a reaching strut because:

- With the afterguy riding across the sheave in the end of the strut, the pole is much easier to control and adjust. Eliminating the friction is important.

- The line will chafe as it rides across the lifeline, stanchions, etc. Decent line for sheets and guys starts at about 75 cents a running foot, and the good stuff at twice that. Unnecessarily replacing it gets old in a hurry.

- The load on the afterguy can be significant if it’s blowing. That can and will bend the lifeline and stanchions.

- Crew on the rail will be safer and happier without a loaded (and possibly weak) guy on their chests or backs.

And, more important – when sailing fairly close to the wind with the spinnaker, the pole is well forward. In a good breeze the afterguy or sheet is very heavily loaded. If that lifeline or stanchion (or both) bends enough, or breaks, the pole will slam forward into the forestay. Bad things can happen. Very bad things.

A reaching strut is easy to rig, and easy to use. Because it’s fairly short, it’s also easy to stow. And not expensive , especially when you consider the cost of a forestay or mast.